My tall English Literature professor wrote “Death of the Author” on the board. He explained that the author’s intent didn’t matter—only the readers’ interpretations. My classmates nodded along, scribbling notes. I couldn’t stay silent. I stood up and asked, “Are you saying there’s no right answer when it comes to interpreting literary texts?”

“That’s correct,” he replied, crossing his arms and leaning on a desk.

“Then how will you grade our exams if there’s no right answer?”

Some classmates gasped, while others rolled their eyes. My professor stood up straighter and said, “It will depend on how well you defend your interpretation.” But that wasn’t true. He clearly valued his own interpretations, and those were the ones everyone tried to copy on exams.

My Korean classmates were often shocked by my openness to debate with professors. They labeled me the weird overseas student. In a Confucian, collectivist culture, questioning teachers—or standing out in any way—was frowned upon. After three years at Seoul National University, I was burnt out from the constant reverse culture shock.

“I want to quit college. I want to leave Korea,” I told my parents over the phone. They suggested taking a year off to volunteer as an English teacher at an NGO they knew in Mexico. In January 2013, I boarded a flight to the southernmost part of Mexico, near the border with Guatemala. From there, the school director picked me up, and we drove four more hours into the mountains to a small, remote village.

In the following weeks, I met all the staff members at the NGO, but one person in particular always got on my nerves. He was tall, slender, athletic—and an unapologetically patriotic American who questioned everything I said. Our first interaction was over lunch. Steam rose from fresh tortillas, mixing with the rich aroma of simmered beans and grilled beef. The cafeteria hummed with Spanish conversations as plastic chairs scraped against tile floors.

“So, where did you grow up?” he asked.

“Paraguay, Spain, and China,” I replied, already anticipating his next question.

“Which country did you like best?” he asked casually, taking a bite of his tortilla.

I shrugged. “Every country is so different. I think—”

He cut me off. “Well, I think America is the best country in the world.”

I shuddered. I’d met plenty of Americans who believed that the U.S. was the center of the world, and I usually ran away from them as fast as I could.

“You know, technically, it’s not America. It’s the United States. America belongs to people in both South and North America,” I said irritably.

“Yeah, yeah. That’s what South Americans say,” he replied, taking another casual bite.

Our conversation was over.

However, in the isolation of our mountain campus, with spotty internet and few other young staff members, our paths kept crossing. Soon our evenings filled with guitar lessons, Bible studies, and the occasional precious trip to Walmart for pizza.

Gradually, I learned more about him. I was captivated by this man’s boldness in the authority of Scripture and his broad worldly knowledge. When I was struggling with a past sin, he said, “Let it go. The Bible says that Jesus forgave your sins. Who are you to keep dwelling on what God has forgotten?”

He also had a gift for teaching—whether it was the Bible or anything else. Once, he even brought out a whiteboard and taught me Economics 101 in a way I had never understood before. It wasn’t long before we started falling in love.

But I couldn’t let myself fall in love with him. Sure, he met all the criteria on my list for a future husband (Science major? Check. Loves to read? Check. Pursues the Lord? Check.), but I couldn’t envision how our future would work. We were from completely different worlds. He planned to return to America after his time in Mexico, while I intended to go back to Korea. His vision was to help develop the economy of a struggling country, whereas mine was focused on teaching and education. And whenever we talked, we clashed. Our backgrounds and ways of thinking were just too different.

As an English major, it felt natural to express my doubts through a poem—explaining why I didn’t think our relationship would work. This is what I wrote.

Travelers

Two travelers met in a wood.

But each knowing what they were,

Silently accepted the fact

That they won’t be on the same road

For long.

Two travelers sat down to eat.

But each coming from the ends of the earth,

Humbly opened their sacks

To share the different food

They had.

Two travelers made small talk.

But each were surprised to find out that

They couldn’t hear each other

For the wall of difference was too high

Between them.

Two travelers lay down to sleep.

But each wishing for more than a nod,

Looked at the starry night high above

Because the sky was the only common thing

They shared.

Two travelers got up with the sun.

But each hesitating to continue the lonely walk,

Looked at each other long

And waited for the other to motion to

The same road.

Two travelers turned to leave.

But each being too polite to ask,

Held on to the mere memory of their faces,

Hoping their paths would cross

Once more.

He didn’t say anything at first, and his silence terrified me. Then, a reply arrived in my inbox—the same poem I had written, but with the last two stanzas revised. This is what he wrote.

[…]

Two travelers turned to leave.

But each loathing decorum,

Mustered the courage in the face of danger

And sought to ask what each was waiting

To hear.

Two travelers loosened their lips to speak.

But each saying to hell with their plans,

Asked in unison if they could

Join them on their glorious

Adventure.

I laughed and cried. For one, I was amazed that he responded with a poem (he had never written one before). And I was challenged by his boldness—the boldness to pursue a relationship he believed was God-given, and to chase his dreams and bring them to life. We spent countless hours under starry skies, painting a picture of what our future could be. He said, “We can still change the world together, Sharon. You in the education sector, and me in the business sector. How about that?”

When we got married four years later, I remember crying with thanksgiving. I had a very specific list of criteria for my future husband (a science major—what?), but God gave me someone who was so much more than that.

God addressed both my loneliness as a perpetual foreigner and my yearning for global impact in my husband. Having moved frequently himself, he understood the unique ache of constant goodbyes and the exhilarating pull of new horizons. (My husband later confessed that he acted like a patriotic American just to annoy me on purpose—a dating strategy, apparently.)

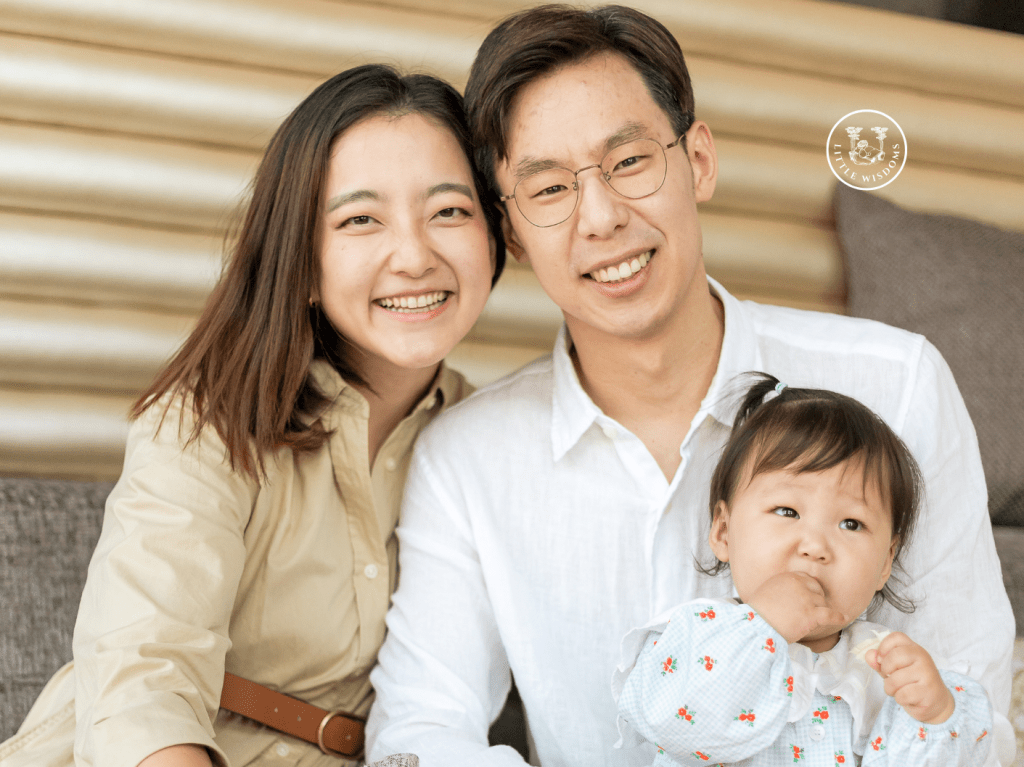

Though we came from worlds apart, God was our common denominator. Faithful and kind, He led us to one another, fulfilling the deepest desires of our hearts, as expressed in Psalm 145:16: “You open your hand; you satisfy the desire of every living thing.” My husband and I have become more alike—both in personality and, surprisingly, in appearance.

What started as two travelers on separate paths has become one beautiful, complicated, God-centered adventure.

P.S. Below is a picture from our time in Mexico, taken during our visit to Cañón del Sumidero—a beautiful canyon in the state of Chiapas, where we lived. Ten years later, we are looking much more alike.

Leave a comment